The American founders could teach Putin a lesson: Provoking an unnecessary war is not how to prove your masculinity

There are lots of official photos of Russian President Vladimir Putin shirtless, including this one from August 2017.

Alexey Nikolsky/SPUTNIK/AFP via Getty Images

Maurizio Valsania, Università di Torino

President Vladimir Putin of Russia loves shows of machismo. He constantly pumps up his swagger. He is wont to disparage women. And he has repeatedly appeared on the public stage bare-chested or as a formidable judo athlete.

Putin likely carries out such performances for a series of reasons: to reassure himself that he belongs to a group of famous strongmen; to demonstrate his theory that a good leader is one who thrives on flamboyant, unchecked virility; and to show his constituents – including many international acolytes – that male authority isn’t really under threat.

You might laugh at such childish and cartoonish convictions and attitudes. But attitudes sometimes are not just a matter of personal style or political opportunism; they can lead to dramatic global consequences, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Looking at Putin, you could make the case that machismo results in war: For these types of men and leaders, a war seems to offer the ultimate test in masculinity.

As a historian who has spent years writing a book on George Washington’s leadership and masculinity, I have no qualms about stating that, for that long-gone generation that created an independent country, wars didn’t feed their egos.

On the battlefield

The American founders were often misogynists and racists. They could be reckless and brutal. But they didn’t crave wars just to prove that they were real men.

It’s true that Alexander Hamilton once made a shocking confession to a friend, “I wish there was a War.” But that’s precisely the point: He was a 12-year-old boy when he wrote that, not yet a man.

None of the founders were pacifists. Together they built a navy and an army. They studied the art of war by reading Julius Caesar or Humphrey Bland, author of a popular “Treatise of Military Discipline.” They all accepted wars as a necessity, especially when every other option was impractical.

Moreover, they saw war as inevitable because they didn’t trust human nature: “This pugnacious humor of Mankind,” Thomas Jefferson wrote, “seems to be the law of his nature.”

“So strong is this propensity of mankind to fall into mutual animosities,” James Madison had already declared, that “the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions and excite their most violent conflicts.”

The majority of the founders also didn’t shelter in their palaces, as Putin has done, seated at an impossibly long table. “I had 4 Bullets through my Coat, and two Horses shot under me,” George Washington wrote after the battle of the Monongahela River in 1755. “Death was levelling my companions on every side of me.”

Washington, Hamilton and others could be easily found on actual battlefields where countless horrors took place.

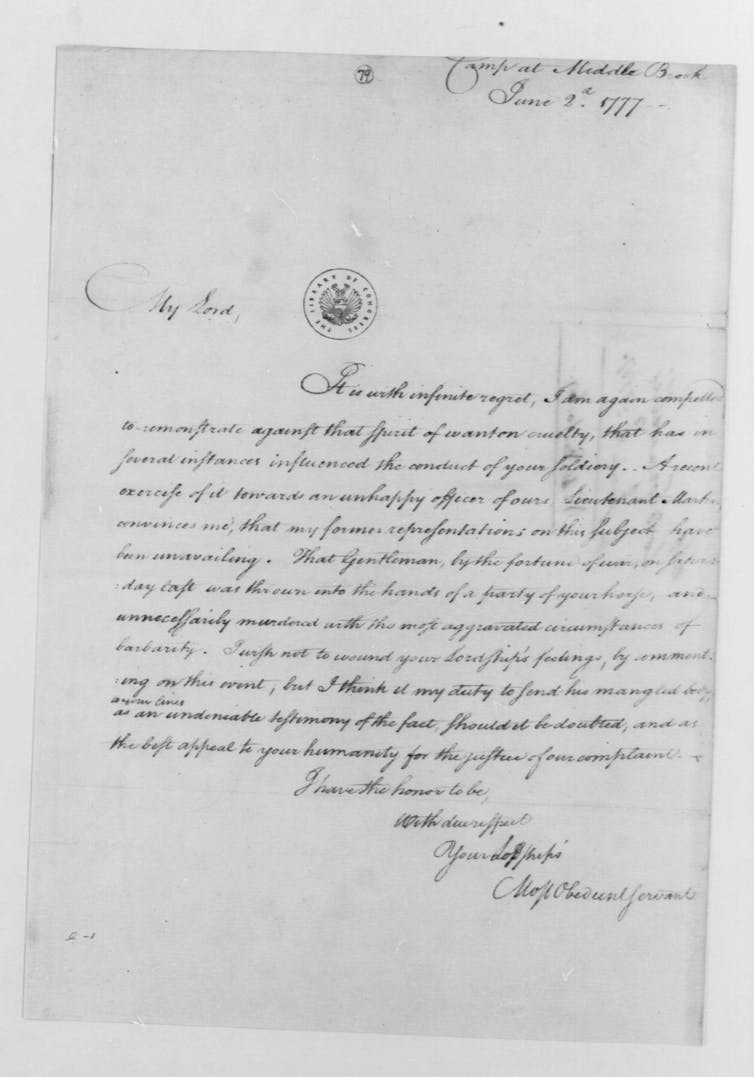

On May 31, 1777, William Martin, lieutenant of Oliver Spencer’s Additional Continental Regiment, for instance, was ambushed by a British-Hessian unit near Bound Brook, New Jersey. Wounded, he asked for clemency, but to no avail. He was “butchered with the greatest cruelty,” wrote one observer. He was bayoneted about 20 times. His nose was cut off and his eyes yanked out.

Washington ordered some soldiers to bring Martin’s body to his headquarters. He had the body washed and shown as proof of the enemy’s inhumanity and lack of virility. Eventually, he sent the body to the British commander, General Cornwallis.

‘Never crave wars’

In the 18th century, the soldier was a good example of a truly virile man, but only provided he kept acting soldierly.

Look at our enemies, Washington exclaimed in a letter to Patrick Henry; look at the spectacle of recklessness they offer. They only bring “devastation,” whether upon “defenceless towns,” or “helpless Women & Children.” His conclusion was clear: “Resentment & unsoldiery practices” have “taken place of all the Manly virtues.”

Walking the razor-thin line between real and pretended masculinity isn’t easy. But 18th-century leaders knew what had to be avoided at all costs. Only “Unmanly Men,” Benjamin Franklin realized, would “come with Weapons against the Unarmed.” They would “use the Sword against Women, and the Bayonet against young Children.”

Manly men, in fact, put up with wars; but they never crave wars, let alone provoke wars, according to the American founders. A virile man, especially a soldier, must be propelled by the vision of an intellectual, cultural and moral refinement: “I must study Politicks and War,” John Adams once wrote, so that “my sons may have liberty to study Mathematicks and Philosophy.”

Thomas Paine, the author of influential political pamphlets, would articulate the same idea: “If there must be trouble, let it be in my day, that my child may have peace.”

That inspiring image of children reaping the fruits of peace — definitely at odds with Putin’s shows of bravado through the years — is taken from the Bible. But the image has a political bent and doesn’t belong to any specific religion: People shall “beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning-hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.”

Washington, a man and a leader graced with a hefty dose of masculinity, agreed completely: “That the swords might be turned into plough-shares, the spears into pruning hooks — and, as the Scripture expresses it, the nations learn war no more.”

[More than 150,000 readers get one of The Conversation’s informative newsletters. Join the list today.]

Maurizio Valsania, Professor of American History, Università di Torino

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.